The Making of The Fabric of Home: Quilts that Tell Stories of Housing Insecurity

“The Fabric of Home" is a reflection on the fragility and transience of stability, drawn from intimate interviews with families affected by housing insecurity. It explores the toll of constant displacement, the wear on both physical and emotional landscapes, and the resilience required to recreate a sense of home amid upheaval.

When Hannah Fairbrother, Lecturer in Public Health at Sheffield University, reached out to me, she was leading a project that explored housing insecurity among families—those facing or at risk of repeated, involuntary moves, often tied to poverty. Her research involved qualitative interviews with families, capturing deeply personal stories of displacement and its impact on daily life. Hannah wanted to commission quilts that could convey these lived experiences alongside her findings, adding a tactile, visual dimension to the families' narratives.

Having attended one of my online courses, Hannah was drawn to my description of quilting: “A quilt is an object that offers comfort and protection—just as the act of making it comforts and protects me. A soft fabric hug that connects me to its eventual recipient; fabrics with memories that are passed on to create new ones.” This idea resonated deeply with the aims of her project. After a successful funding bid from the ESRC Festival of Social Science, we set out to create The Fabric of Home, a collection of quilts that tell stories of resilience, instability, and the fragile nature of ‘home’ for many families.

Initial Ideas

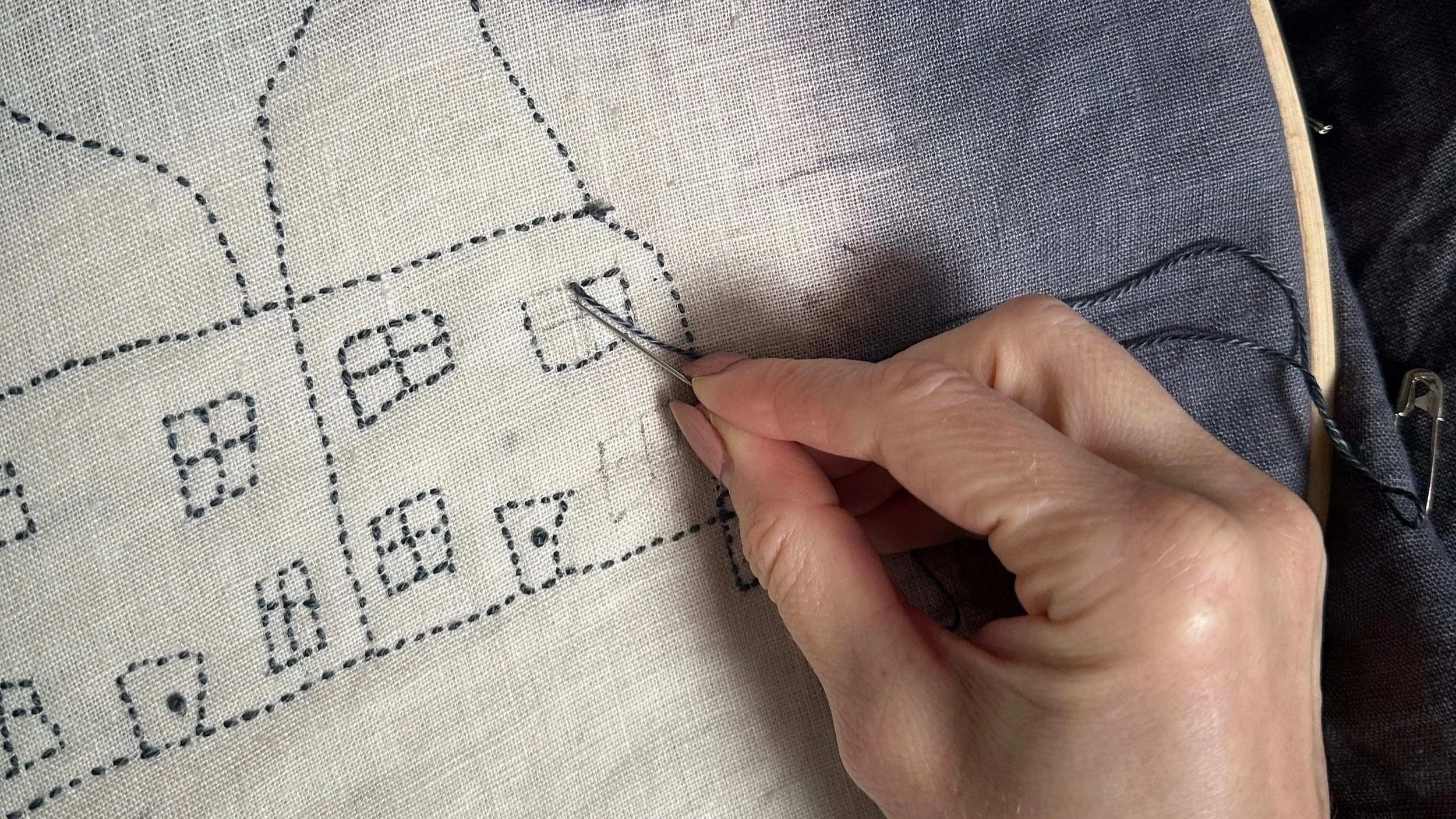

My first thoughts stemmed from the parallels between fabric mending as an act of care and the restoration of a family’s sense of home. As I read through the interview transcripts, I noted words and phrases that resonated with me—many carrying a strong tactile quality, like “torn from the family home” and “fabric of society.” These expressions felt perfectly suited to textile techniques such as patching and mending, echoing the themes of repair and resilience. Among the materials, I was especially moved by children’s drawings included in the interviews, and I knew early on that I wanted to incorporate these in the work. From these starting points, I mind-mapped ideas, imagining how textile processes could capture these experiences.

Translating a child’s drawing into stitch

The Quilts

The distressed fabrics used in these quilts—worn, torn, and imperfect—are reminders of the often unsuitable, unsafe conditions in which many displaced families find themselves. They speak of damp, mould, and the degradation of what should be safe spaces, turning them into places of harm and insecurity. These textures highlight the harsh reality that not all shelter is stable or safe, and that for many, the places they must call "home" are deeply compromised.

Many of the fabrics used are repurposed domestic fabrics—some passed down from my grandmother and used by my daughter. As the work evolved, so too did my personal connection to it. These materials, rich with the memory of my own family, became a canvas on which I reflected on the ties that bind us, despite the ruptures caused by instability. The fabrics themselves carry the weight of continuity and memory, much like the families whose stories are embedded in the work.

I used dyes made from kitchen waste—onion skins, avocado pits, and sumac leaves from my garden—further embedding the quilts with a connection to my home and family. This process of making dyes from what would otherwise be discarded echoes the resilience of these families, who find ways to rebuild and sustain themselves, even in the face of adversity.

The act of mending—through darning, applique, and boro techniques—became a metaphor for repairing the family home. As I stitched, I thought about how repairing fabric mirrors the work these families do to restore a sense of stability. Just as torn fabric is mended, homes can be rebuilt, but the scars remain, visible yet stronger for having been tended to. This visible repair speaks to the resilience that emerges from hardship, showing that the process of healing can itself be a source of strength.

Through layers of texture, frayed edges, and stitched patches, I’ve attempted to capture the uneven nature of these lived experiences. The irregularity in the fabric is a metaphor for the instability families face, a reminder of the fractured environments where safety is precarious, and the notion of 'home' is frequently dismantled and reassembled. These quilts are a patchwork of those stories, a tactile chronicle of displacement, resilience, and the enduring hope for a permanent place to belong.

The Fabric of Home - Main Quilt

103cm x 130cm

Plant dyed repurposed linen and cotton domestic fabrics.

The quilt’s patchwork of shapes, textures, and tones symbolises the fragmented nature of displacement. Darker, fading sections evoke uncertainty, while warmer, hand-dyed fabrics represent the lingering memories and emotional ties that persist even in the face of loss. There are nods to physical structures—houses and walls—that should protect, yet can so easily become fragile and unsafe.The interviews profoundly affected me, particularly the experiences of children who have had to adapt to frequent relocations and the immense mental load carried by parents. Hearing their stories made the reality of instability deeply personal. It became clear that the strain of such uncertainty reaches beyond the physical—into the very core of familial relationships and emotional well-being.

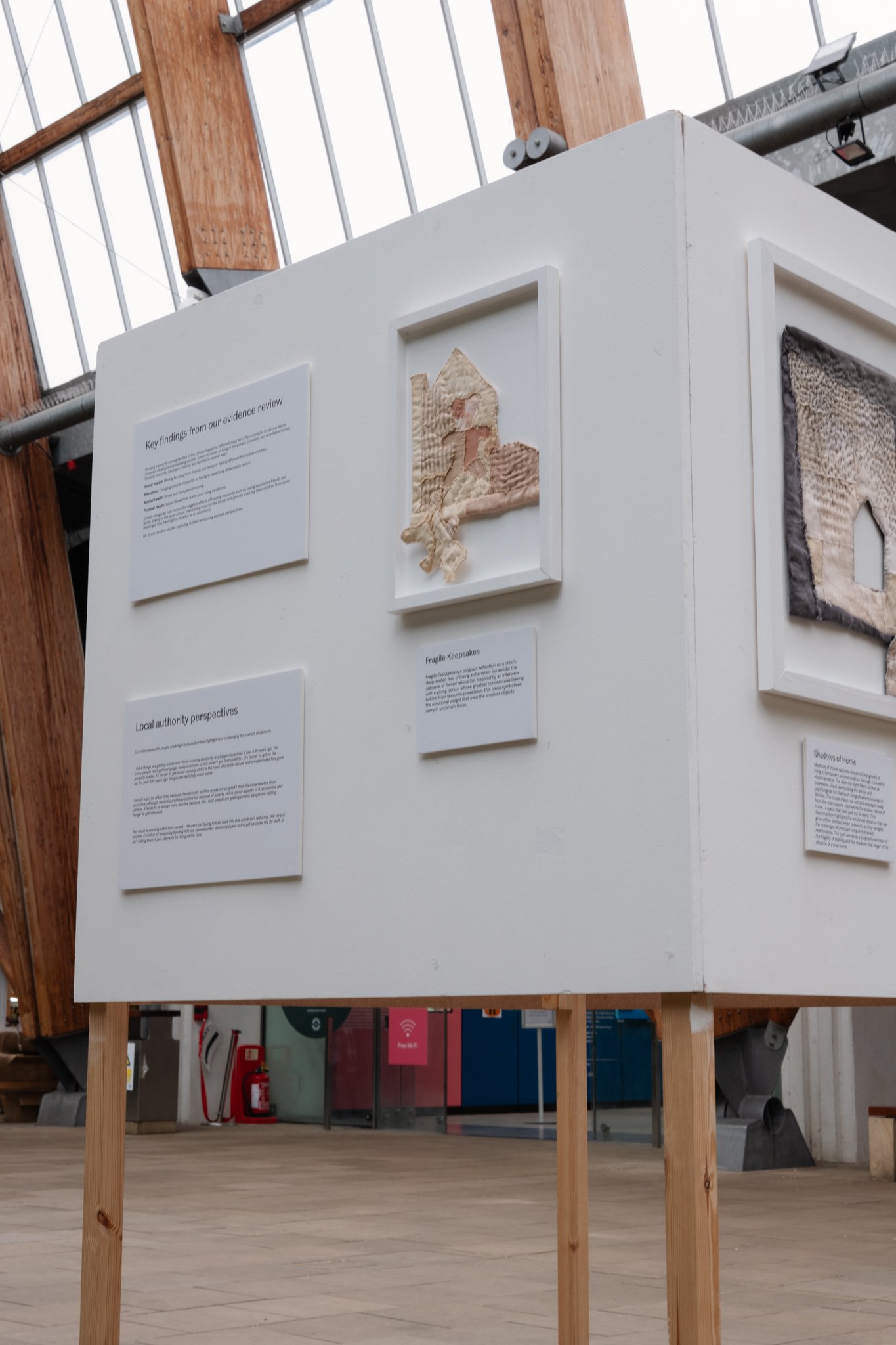

Fragile Keepsakes

26cm x 32cm

Plant dyed linen and cotton

’Fragile Keepsakes’ is a poignant reflection on a child’s deep-seated fear of losing a cherished toy amidst the upheaval of forced relocation. Inspired by an interview with a young person whose greatest concern was leaving behind their favourite possession, this piece symbolises the emotional weight that even the smallest objects carry in uncertain times. (A4 landscape)

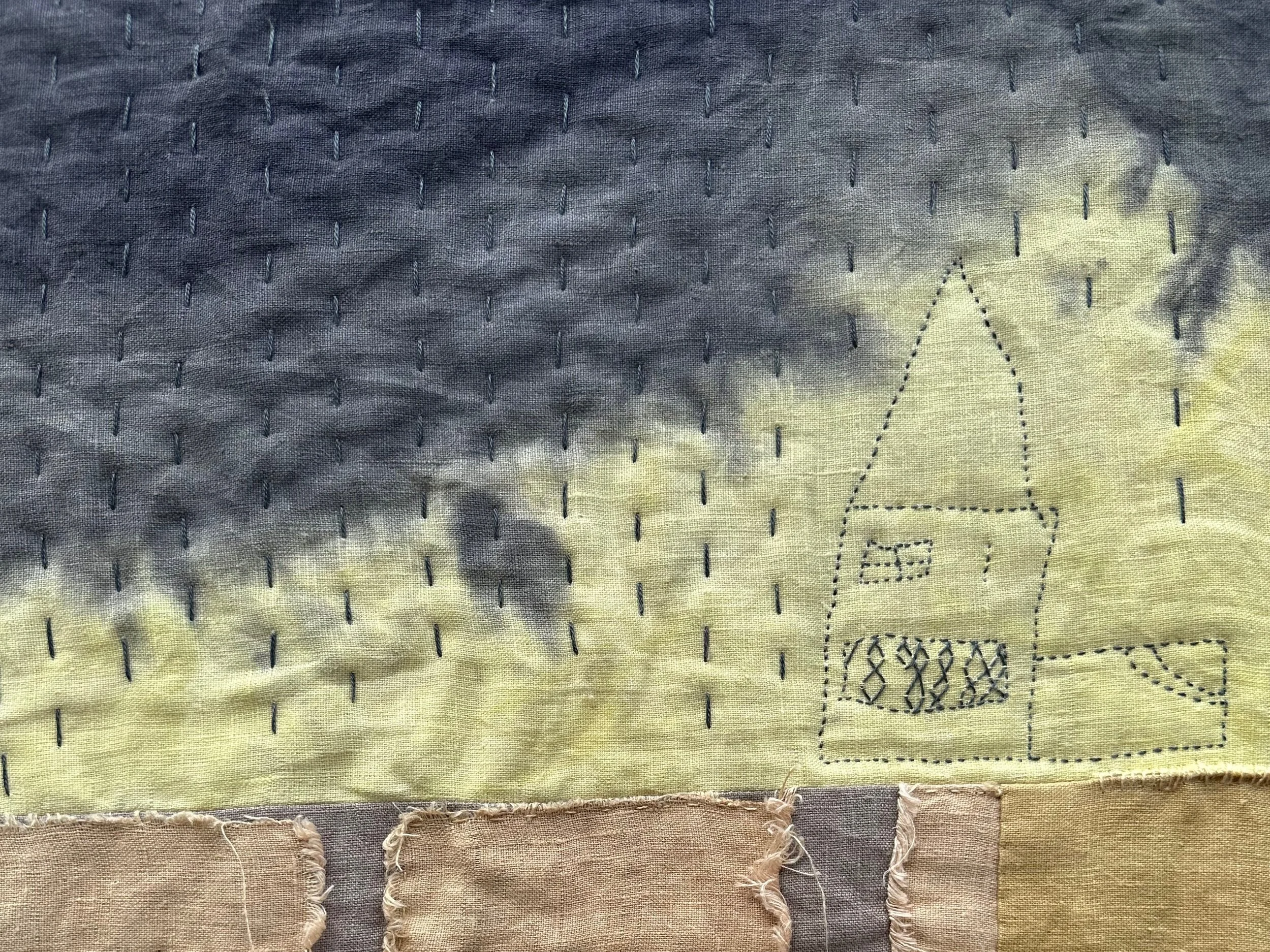

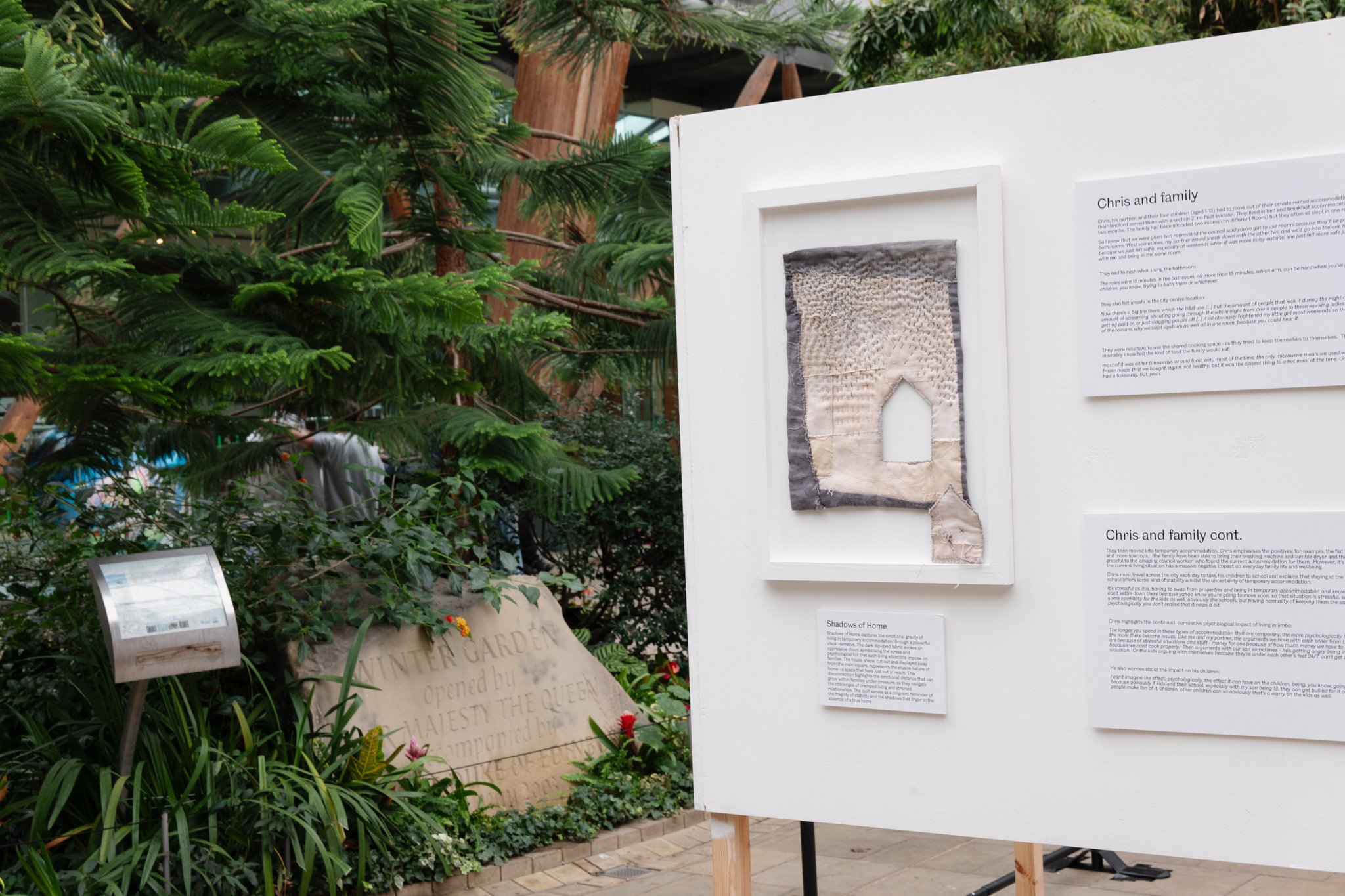

Shadows of Home

39cm x 30cm

Plant dyed linens and cottons, modified with iron.

‘Shadows of Home’ captures the emotional gravity of living in temporary accommodation through a powerful visual narrative. The dark dip-dyed fabric evokes an oppressive cloud, symbolising the stress and psychological toll that such living situations impose on families. The house shape, cut out and displayed away from the main square, represents the elusive nature of home—a space that feels just out of reach. This disconnection highlights the emotional distance that can grow within families under pressure, as they navigate the challenges of cramped living and strained relationships. The quilt serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of stability and the shadows that linger in the absence of a true home.

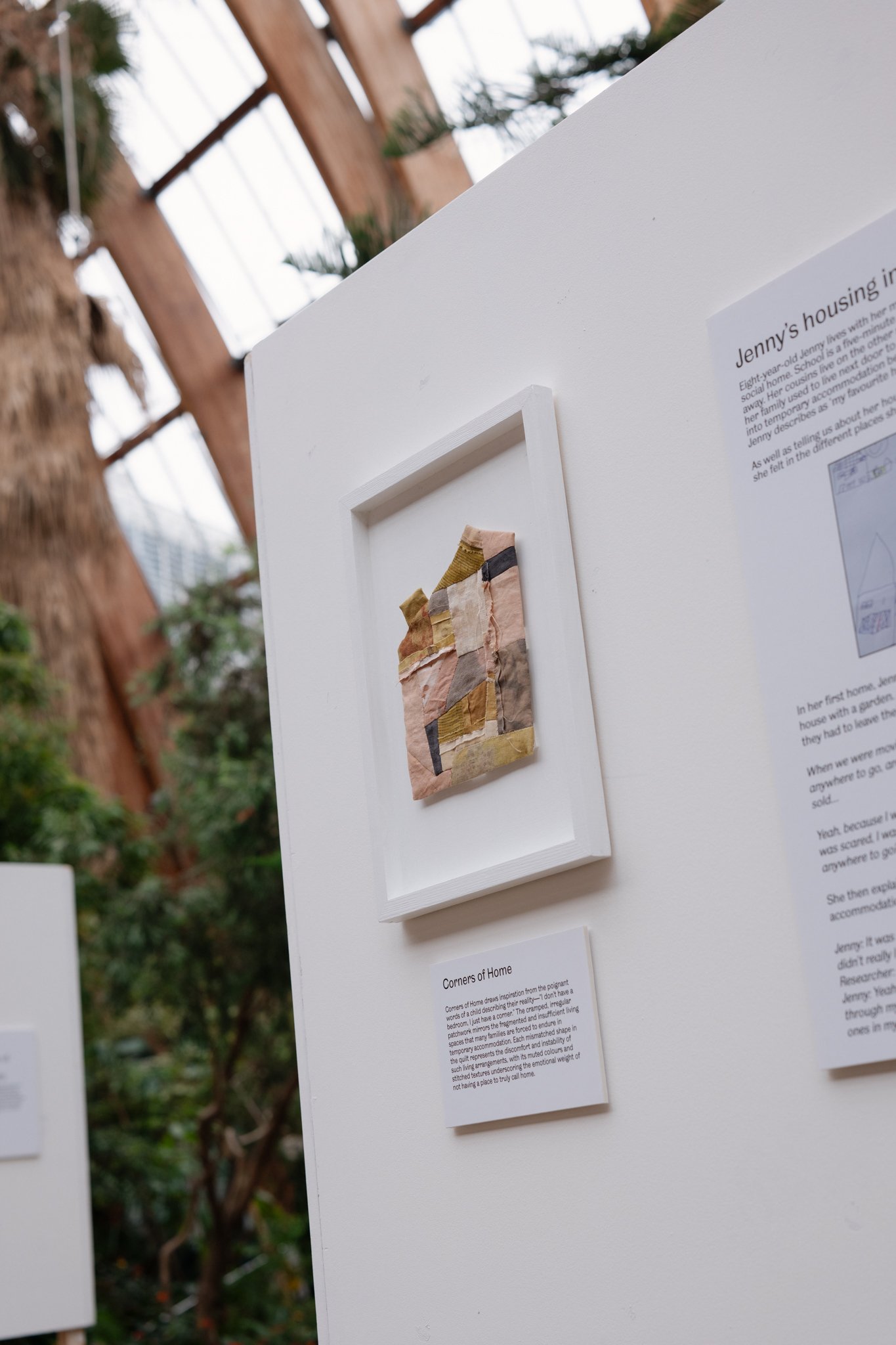

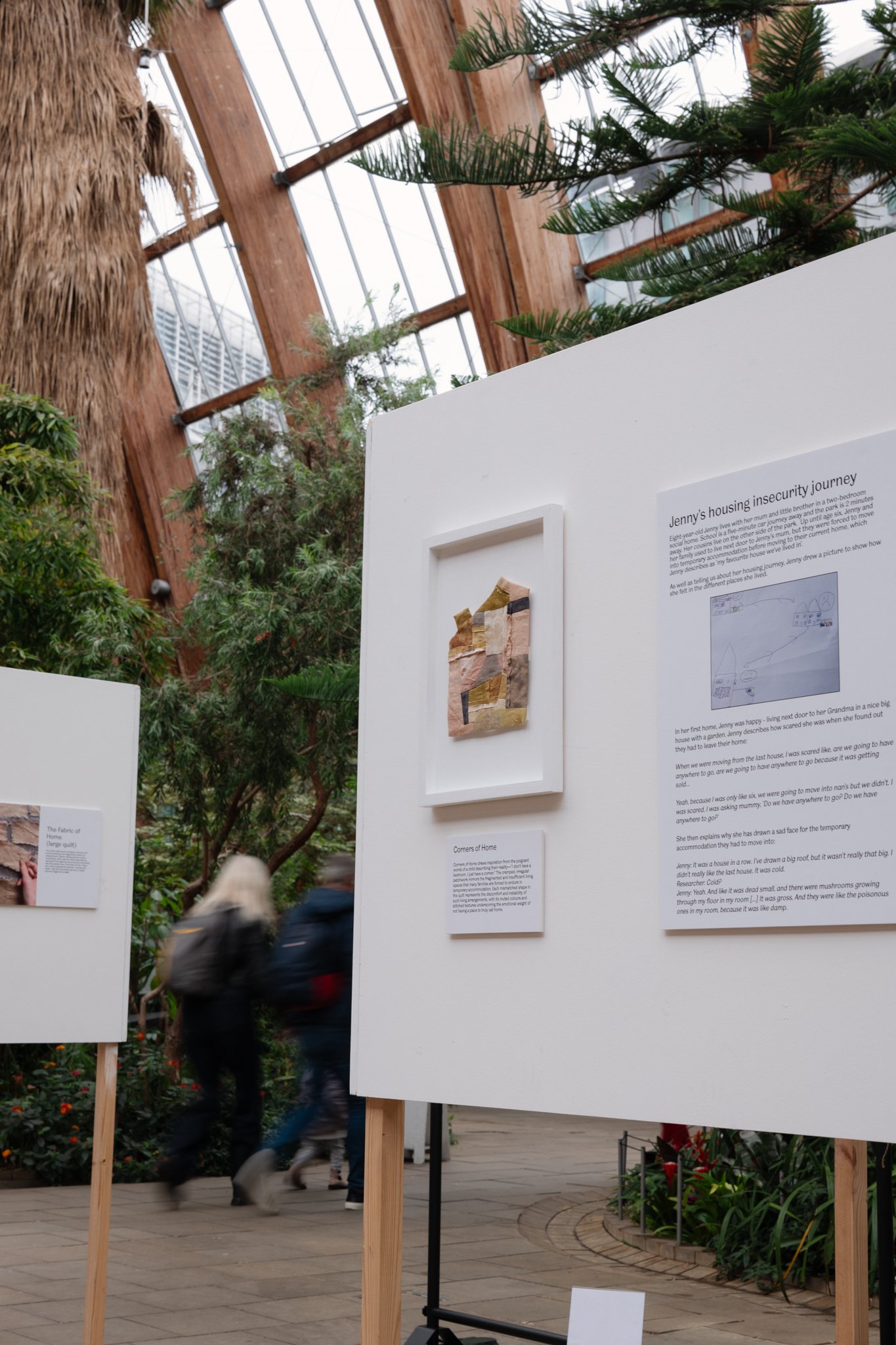

Corners of Home

17cm x 23cm

Plant dyed linen and cotton offcuts.

’Corners of Home’ draws inspiration from the poignant words of a child describing their reality—"I don't have a bedroom, I just have a corner." The cramped, irregular patchwork mirrors the fragmented and insufficient living spaces that many families are forced to endure in temporary accommodation. Each mismatched shape in the quilt represents the discomfort and instability of such living arrangements, with its muted colours and stitched textures underscoring the emotional weight of not having a place to truly call home.

Threads of repair

16cm x 22cm

Plant dyed linens and cottons

‘Threads of repair’ explores the delicate relationship between damage and repair within the context of a home. The visible hole in the structure, meticulously darned, serves as a metaphor for the emotional scars left by hardship and instability. Just as the fabric is carefully mended, this piece speaks to the process of healing from emotional wounds—slow, imperfect, but resilient. The patched area is both a reminder of what was once broken and a testament to the strength found in the act of mending, reflecting the resilience that individuals and families develop in the face of uncertainty.

The Research

Shared with permission from Hannah Fairbrother, Sheffield University

In the UK today, many families live with housing insecurity - they do not have a stable, safe or affordable place to live.

Housing insecurity can encompass a range of situations, including:

Rent burden - spending a significant portion of income on rent, making it difficult to afford other necessities.

Eviction risk - facing the threat of being forced out of one's home due to unpaid rent or other violations of a lease agreement.

Overcrowding - living in a space that is too small for the number of people residing there.

Poor housing quality - living in a dwelling that is unsafe, unhealthy, or in disrepair.

A shortage of social homes, rising rents, the cost-of-living crisis and the growing unaffordability of home ownership all mean that more and more families are experiencing housing insecurity and many are living in temporary accommodation.

This exhibition shares recent research exploring families’ experiences of housing insecurity alongside a series of fabric quilts by textile artist, Rebekah Johnston, reflecting on key themes from the research like safety, connection, shelter and protection. A quilt is an object that offers comfort and protection - just as the act of making it comforts and protects the artist. A soft fabric hug that connects the artist to its eventual recipient; fabrics with memories that are passed on to create new ones. In this way, quilts have real parallels with home - somewhere that should offer comfort and protection and a ‘hug’ for the people who live there.

Lead researcher: Hannah Fairbrother, Senior Lecturer in Public Health, University of Sheffield

Textile artist: Rebekah Johnston

A review of research evidence about the impact of housing insecurity on children’s health and wellbeing

The exhibition draws on two recent research projects that focus on families’ experiences of housing insecurity

We brought together findings from qualitative literature (studies that focus on people’s experiences and perspectives) exploring the relationship between housing insecurity and the health and wellbeing of children and young people (aged 0-16) in the UK.

Studies included the perspectives of children themselves, parents / close family members (e.g. grandparents) and other people with insight into children’s experiences (e.g. teachers).

We integrated accounts of housing insecurity within 59 pieces of evidence from studies conducted over the UK as a whole and specific locations including London, Birmingham, Fife, Glasgow, Leicester, Rotherham and Doncaster, and Sheffield.

Project team members: Emma Hock (lead), Lindsay Blank, Hannah Fairbrother, Mark Clowes, Diana Castelblanco Cuevas, Andrew Booth & Elizabeth Goyder

Project funder: National Institute for Health and Care Research Public Health Research Programme.

A study with children, parents and local authorities to explore experiences and drivers of housing insecurity

We carried out over 70 interviews with children, parents and local authority colleagues across South Yorkshire, the North West and London.

We asked about:

Current experiences

Factors driving housing insecurity

Local authority approaches to tackling housing insecurity and supporting families

Project team members:

University of Sheffield: Hannah Fairbrother (lead), Mary Crowder, Ellie Holding, Nick Woodrow & Elizabeth Goyder

University of Birmingham: Kiya Hurley, Sophie Hadfield-Hill & Peter Kraftl.

University of Cambridge: Anne-Marie Burn (co-lead)

University of Liverpool: Sarah Rodgers (co-lead), Jamie O’Brien

Project funder: National Institute for Health and Care Research School for Public Health Research

A review of research evidence about the impact of housing insecurity on children’s health and wellbeing.

Key Findings

Housing insecurity among families in the UK can take many forms and result from several situations, which often relate to each other, including being evicted or forced to move and living in temporary/crowded/unsuitable accommodation.

Experiencing housing insecurity can negatively impact children and families in many ways:

Socially (e.g. having to move far from friends and family, feeling different to other children)

Education (e.g. having to join a new school / travel a long way to school)

Mental health and wellbeing (e.g. worrying about having to move)

Physical health (e.g. asthma related to poor housing conditions)

Some things can help to lessen the negative impact of housing insecurity including friendship and support, staying at the same school, hope for the future, and parents protecting their children from some of the impacts (e.g. by turning it into an adventure).

The negative impacts of housing insecurity may be made worse by specific situations and life circumstances, including escaping domestic violence, being a migrant, refugee or asylum seeker (or having a parent with that status), and being forced to move home due to a planned demolition.

However, we found that there are few studies that have actually explored children and young people’s own perspectives of housing insecurity and this led to our second project.

A parent’s perspective on housing insecurity

Chris, his partner and their four children (aged 1-13) had to move out of their private rented accommodation when their landlord served them with a section 21 no fault eviction. They ended up living in bed and breakfast accommodation for two months:

“‘So I know that we were given two rooms and the council said you’ve got to use both rooms because they’ll be paying for both rooms. We’d sometimes, my partner would sneak down with the other two and we’d go into the one room because we just felt safer, especially at weekends when it was more noisy outside, she just felt more safer just being with me and being in the same room.’”

They then moved into temporary accommodation and Chris highlights the continued, cumulative psychological impact of living with housing insecurity:

“‘The longer you spend in these types of accommodation that are temporary, the more psychologically it affects you, the more there becomes issues. Like me and my partner, the arguments we have with each other from time to time are because of stressful situations and stuff, money for one because of how much money we have to spend because we can’t cook properly, then arguments with our son sometimes, he’s getting angry being in the situation, or the kids arguing with themselves because they’re under each other’s feet 24/7, can’t get out’.”

Jenny’s housing insecurity journey

Eight year-old Jenny lives with her mum and little brother in a two-bedroom social home. School is a five minute car journey away and the park is 2 minutes away. Her cousins live on the other side of the park. Up until age six, Jenny and her family used to live next door to Jenny’s mum but they were forced to move into temporary accommodation before moving to their current home, which Jenny describes as ‘my favourite house we’ve lived in’.

As well as telling us about her housing journey, Jenny drew a picture to show how she felt in the different places she lived. In her first home, Jenny was happy - living next door to her Grandma in a nice big house with a garden.

Jenny describes how scared she was when she found out they had to leave their home:

“When we were moving from the last house, I was scared like, are we going to have anywhere to go, are we going to have anywhere to go because it was getting sold…Yeah, because I was only like six, we were going to move into nan’s but we didn’t. I was scared, I was asking mummy, ‘Do we have anywhere to go? Do we have anywhere to go?”

She then explains why she has drawn a sad face for the temporary accommodation they had to move into:

Jenny: It was a house in a row. I’ve drawn a big roof, but it wasn’t really that big. I didn’t really like the last house. It was cold.

Researcher: Cold?

Jenny: Yeah. And like it was dead small, and there were mushrooms growing through my floor in my room. The only reason that we found out was that mushrooms started to grow on my rugs, because, well, one of my books fell off my shelf near my bed, and then it fell into a wet bit, and I was like, why is it wet? And when I picked it up it was dead wet. And I just called mummy, and told her, and we looked at it, and we’d seen there was mushrooms. It was gross. And they were like the poisonous ones in my room, because it was like damp.

She goes on to describe how they ended up not being able to use her room, the larger room, as it was so damp.

Ariam and Soliana

Ariam and Soliana are sisters. They live with their mum and younger sister. They are currently in temporary accommodation, living in one room in a hostel where they have shared use of bathrooms, kitchen and dining area. They have been at the hostel for more than two-and-a-half years.

There is a park close by that they visit and enjoy and it is easy to get to the shops. They didn’t change schools when they moved to the hostel and the journey to school is long, involving two buses – although neither complained about this.

Overall, both girls feel very negatively about their current living situation. In particular they really dislike having to share bathroom facilities.

Ariam: sometimes the toilets are stinky, and our room is right in front of the toilet and then we smell it from our rooms, so we have to clean it up ourself.

Solina: When you just wanna like maybe have a shower, like you just can always get the disgusting smell. There’s maybe pooh rubbed all over, maybe dirt or leaves, it’s not nice.

Lack of space to study is another important concern, particularly for Ariam who has more homework to do now that she is at secondary school. The family room has no room for a table so her choices are to study on the bed or to use the shared kitchen:

“I mean like put a bin bag or something on the floor and then you work on the floor or work on the bed……... Like I have to do it on the floor and it’s like uncomfortable. Like revising for exams and things like that it might be a bit more difficult, like for concentration. It’s a small area. Like there’s neighbours outside, maybe babies crying, people in the kitchen talking and shouting like. Things like that, a bit distracting ”

Lack of space in general is something they find difficult – they have to share a cupboard for their clothes and some of their possessions have to be kept in bags. They also worry that their little sister has no place to play.

“Sometimes it’s like difficult for her to play, cos like she came at a young age. Her childhood she has to be like in a really small, cramped space which is personally like. I enjoyed my childhood, but she has to be like in small spaces, not much place to play, you can’t run around in the kitchen, cos that’s where people cook. It’s dangerous, inside the bedroom, it’s not really suitable. ”

They are aware that their current living situation is ‘temporary’, are finding it difficult to deal with the uncertainly of not knowing how long they will have to stay, and feel like more housebuilding is needed to improve their chances of finding a secure home.

“I didn’t want to leave. I thought we were just gonna be. My dad said it was was just gonna be here for the weekend and then he said one week and then he said a month, so then we had to stay here for two years.”

“Try like get more houses and its like that easy, it feels like a dream, like imagine more land was made or something like that. A bunch of houses were made, more people would be able to like. Some people here had like five years, six years then like, oh how. I can’t handle being here for three years. I wish they’d like have more land in the country for people to live in.”

Local Housing Authorities Perspectives

Our interviews with people working in local authorities highlight how challenging the current situation is.

I think things are getting worse and I think housing insecurity is a bigger issue than it was 5-10 years go. You know, people can’t get mortgages easily anymore, so you haven’t got that stability… it’s harder to get on the property ladder, it’s harder to get social housing which is the most affordable tenure, and private rented has gone up. So, yeah 5,10 years ago things were definitely much easier.

I would say a lot of the time, because the demands and the issues are so great I think it’s more reactive than proactive, although we do try and be proactive but because of poverty, crime, social aspects of it, economics and all that, it tends to be always more reactive because, like I said, people are getting evicted, people are waiting longer to get rehoused.

Not much is working well if I am honest... We were just trying to hold back this tide which isn't reducing. We we put another £1 million of temporary funding into our homelessness service last year which got us under the 20 staff…it isn’t falling back it just seems to be rising all the time.

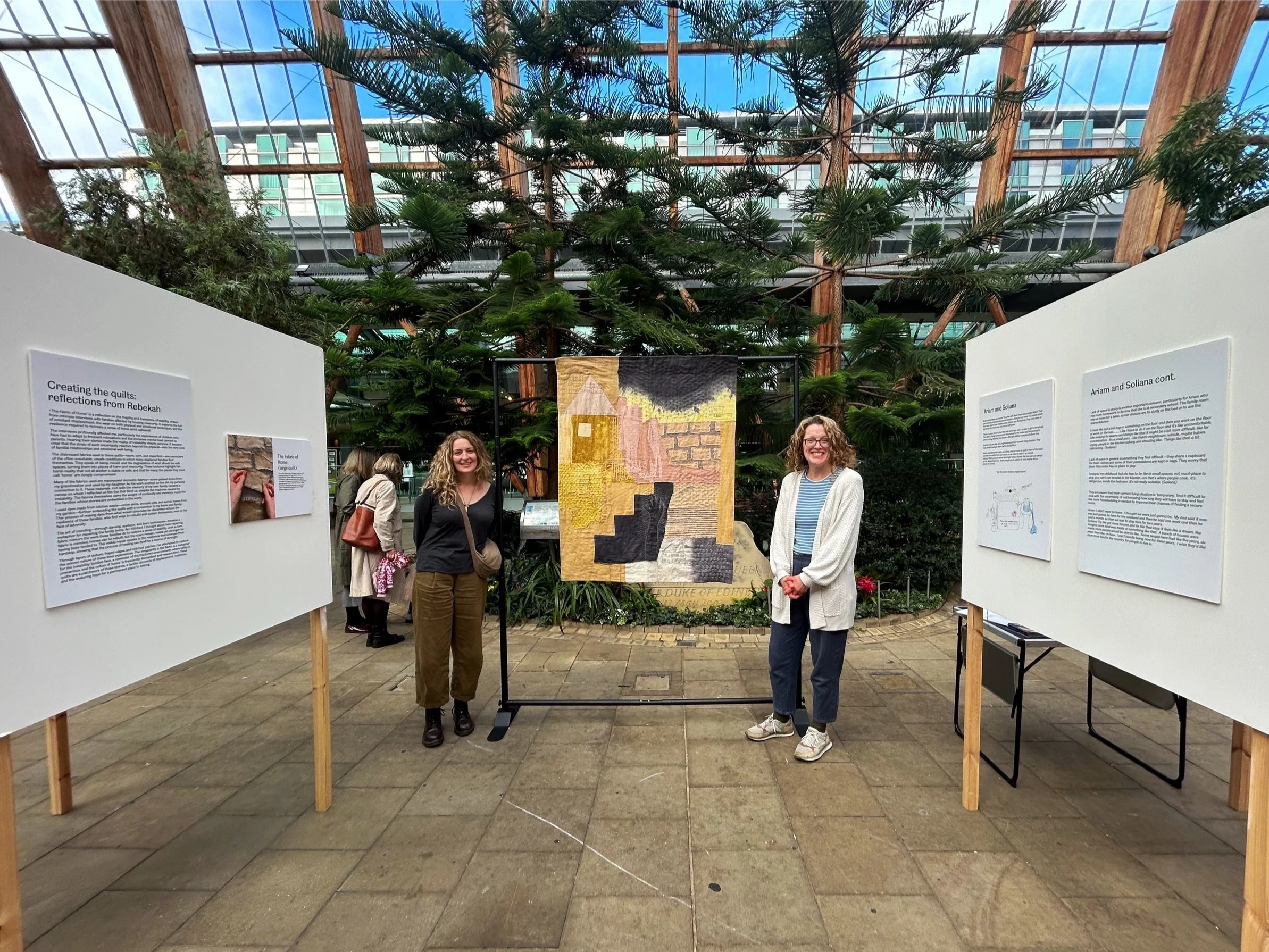

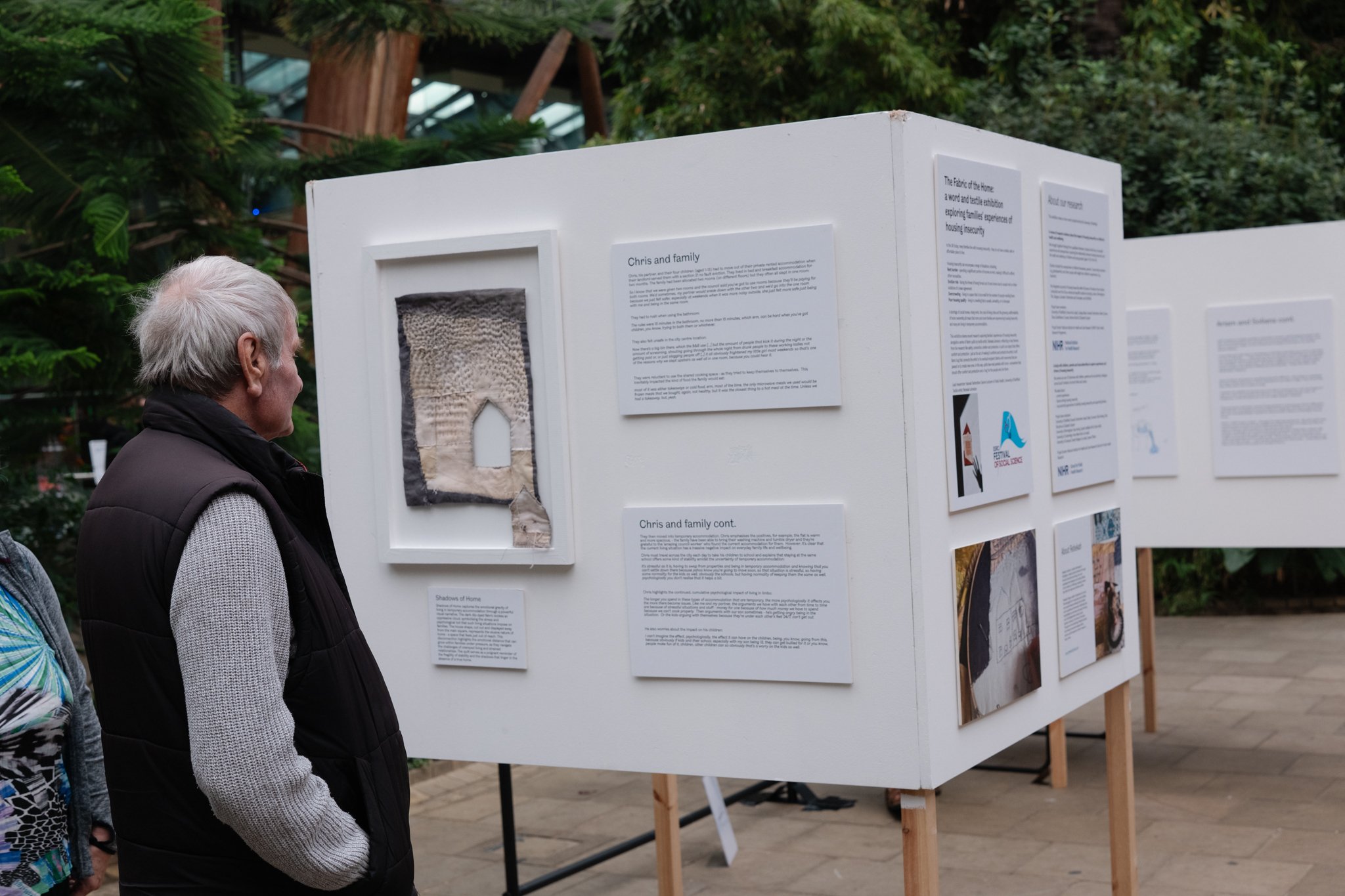

The Fabric of Home in situ at Sheffield Winter Garden.

The Fabric of home is on display at Sheffield Winter Garden from Tuesday 29th October to Tuesday 5th Novemeber

Links to support for those experiencing housing insecurity

If you are currently experiencing housing insecurity, here are some links to support.

Shelter

https://england.shelter.org.uk/housing_advice

Emergency national helpline 0808 8004444 - call during opening hours if you are homeless, have nowhere to stay tonight, are worried about losing your home, or are at risk of harm or abuse in your home.

Online advice service - for help with your housing rights and the next steps to take in your situation.

Webchat - if you need help to take the next steps, or prefer not to call.

Citizens Advice

https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/housing/

For advice on renting, council tax, homelessness and problems where you live.